Monday was Indigenous Peoples Day. I found myself thinking about the hard-fought wins Indigenous activists have earned in the past year: a judge ordered the Dakota Access Pipeline shut down and drained for further environmental review, tribes in Oklahoma won a major sovereignty case at the Supreme Court, and the Washington football team finally dropped its racist name.

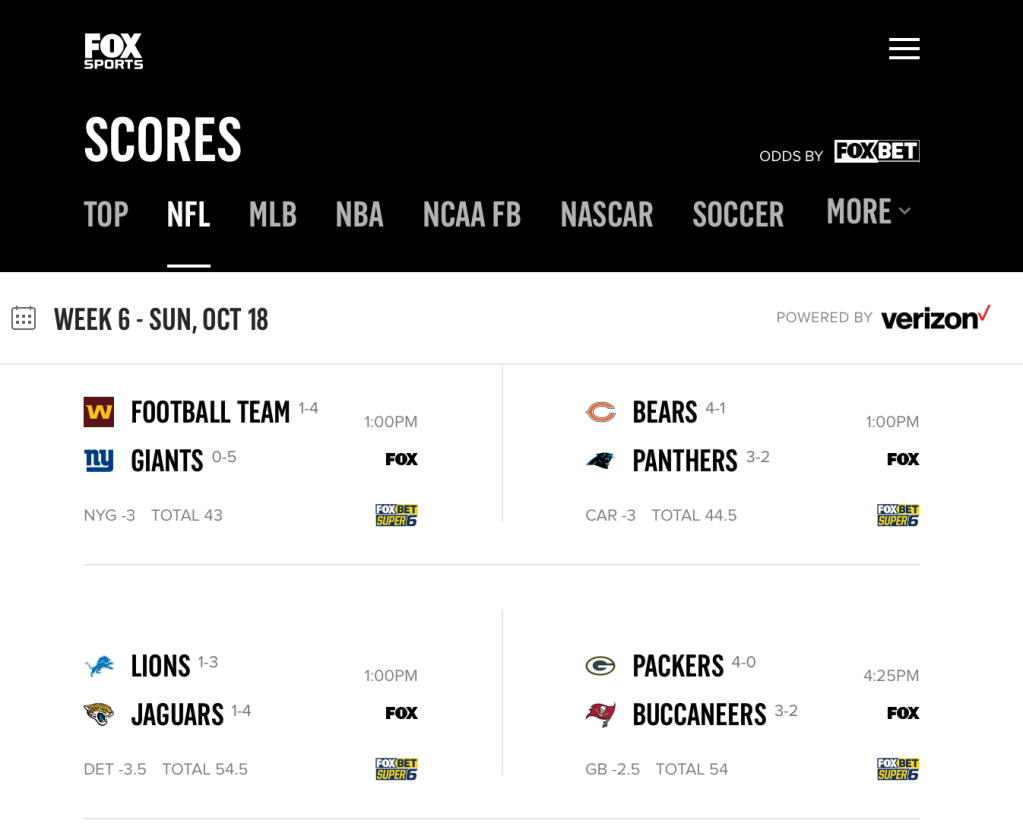

Having lived in Washington for the past 12 years, the constant presence of that team’s logo and name has been a nuisance. The name was (and is, and will be for years to come) on the walls of nearly every bar and restaurant in town, on t-shirts and bumper stickers, on the sides of delivery trucks for wholesome family brands proud to sponsor the team. I’ve never followed the NFL closely, but the name would still pop up on my phone in news alerts when the team was playing important games, or when a star player was injured. Seeing the awkward and absurd use of Football Team, capital F, capital T, as Washington’s nickname across sports media in recent weeks has been a welcome reversal (though the team owner and his corporate culture still have major issues to confront).

• • •

I grew up in Minneapolis, which has the largest urban Indigenous community in the United States. As an adult, I’ve learned that this is due to a policy of forced assimilation by the colonial white government starting in the 19th century, around the time of the city’s founding.

We don’t use the words colonial or colonization when we teach the history of the west and midwest. The U.S. has its thirteen original colonies, but the rest of the country was settled through territorial expansion like a drop of oil naturally pushing outward to cover the surface of water; an inevitable force of nature. Colonization is something those terrible and oppressive nations in Europe did. We heroically asserted independence, the story goes.

I remember the days at the beginning of each school year when I would be issued a new history or social studies textbook. One of the first things I would do is turn to the index and look for mentions of Minnesota and Minneapolis. I suppose I was looking for relevance and meaning, an understanding of my place in the world and the story of where I lived. Often there were no entries. One textbook’s only reference was a quote from a Texas rancher, “there is nothing between the North Pole and Minnesota but fence posts.” Other books would mention the enslaved Dred Scott’s case before the Supreme Court. Scott was enslaved in the south and travelled north with his captor. He met his wife and married in free territory that would later become the state of Minnesota. The court effectively decided that Scott, his wife and child were not human, not worthy of standing before the court, was not who the framers of the constitution had in mind when they said all men are created equal. The textbooks mentioned this, often using fewer than I just used. They might also mention that Walter Mondale and Hubert Humphrey were Minnesotans and Vice Presidents. The textbooks never mentioned the U.S.-Dakota War that took place in Minnesota at the same time as the Civil War. The atrocities approved by President Abraham Lincoln against Native tribes were inconvenient to our learning why the kind bearded man in the stovepipe hat was on the five-dollar bill. And so, the names of territorial officials like Alexander Ramsey and Henry Hastings Sibley who violated treaties and orchestrated racist violence continue to be honored in the names of streets, cities, counties, hospitals, high schools and more. For more on this, I always recommend This American Life’s Little War on the Prairie episode.

The presence of Native American classmates and neighbors in Minneapolis masked for me the true extent of the Indigenous genocide. It wasn’t until I moved to Philadelphia in 2001 that I realized Minneapolis was not representative of the rest of the country.

In Philadelphia, Native Americans were not visible to me as people actively struggling for dignity in the present, as they were in Minneapolis (there are activists from the Lenape and other tribes indigenous to the region who are carrying forward that work). When I saw evidence of Native people in those years, they were solemn parts of the past: one of Earth’s four ancient races carved into stone on City Hall sculptures; a disembodied head on manhole covers on East Passyunk Avenue; anonymous reclining mythical figures in the fountain at Logan Square (a particularly egregious association, given James Logan’s involvement in the land swindle known as the Walking Purchase).

• • •

I learned how to draw by copying things I loved, the visual language around me. I copied Charlie Brown. Snoopy, Garfield the cat and Opus the penguin out of the newspaper’s comics page. I learned the basics of graphic design the same way. I copied the distinctive elements I was most excited about: baseball logos and lettering. What could be more wholesome?

When I learned that the logos of rival teams were repositioned in our air-puffed modern stadium according to the daily standings each morning — something old ballparks like Wrigley Field do using flags — I decided I would do the same on my bedroom wall. I used a full sheet of paper for each team, enlarging the tiny logos in magazines and baseball cards by drawing carefully in light pencil and then coloring and filling in the linework using markers.

Most logos were simple interlocking letters, or a nickname in distinctive lettering with a swoosh. But one team had a stylized grinning dark red face with a feather as its logo. It was just one of the symbols of the game I was growing obsessed with as a kid. Every team had a symbol. This was Cleveland’s. It wasn’t so different from the cartoon Indian that represented the local gas company, or the one on the butter and milk cartons. I copied it out like all the team logos and hung it on the wall. A mundane acceptance, repetition, normalization of racism.

A few years later (1989), the movie Major League came out. Cleveland had been a losing team for decades, and wacky sports comedy made fun of that legacy. The grinning racist logo appears throughout the film. A high school friend, enamored of comedy and sports, adopted the team ironically as his own, going so far as to have the logo shaved into his head. By then, we were old enough to be aware that the logo was “controversial,” but not so self-aware to know that an ironic endorsement was the same as an enthusiastic or intentionally hateful one. A further normalization.

• • •

Under pressure, Cleveland retired the grinning “Chief Wahoo” logo from its uniforms before the 2019 season. This year, around the same time that Washington changed its name to Football Team, Cleveland put out a statement announcing that it was reviewing its use of the name Indians. Now Cleveland’s 2020 season is over. Baseball’s World Series will be over in two weeks. I’m hopeful a name change will follow not long after, and that kids will no longer grow up learning to draw by copying racist caricatures.

You must be logged in to post a comment.